The Night Land has developed a notorious reputation over the years as one of the most forbidding and inaccessible works of classic science fiction. Even H.P. Lovecraft, no stranger to purple prose himself, struggled to make his way through it. “I’m a couple of hundred pages into ‘The Night Land,’” he wrote to a friend in 1934, “but it’s damn hard going. God, what a verbose mess.”

Clocking in at a hefty two hundred thousand words, the Night Land is already dated by the contemporary standards of its 1912 publication date, but rendered still more obscure by its intentionally archaic, faux-Elizabethan prose. Even back in the early twentieth century, this was baroque stuff, rife with artificially mannered and semicolon-laden paragraphs. The author himself knew that the work was a tough slog: When William Hope Hodgson failed to find an American publisher for the original British work, he redacted it to a novella of perhaps a tenth its original size. Nor was the this the last attempt to tame The Night Land. Author John Stoddard put forward a complete rewrite of the work as The Night Land, A Story Retold in 2011.

That was nearly a hundred years after the book’s first publication. There is obviously an enduring appeal to The Night Land, something that continues to bring in new readers who are willing to endure its challenge. Modern fans have composed a significant body of fan-fiction; a comprehensive fan continuity has sprung up on a website that tracks the passing of millions of in-universe years in an ambitious collaborative project. Multiple online communities have speculated about running tabletop role-playing game adventures in the Night Land. Modern writers from Greg Bear to China Mieville have cited Hodgson’s influence, and at least one collection of completely original, unauthorized Night Land stories has been put up for sale on Amazon. Fans are quick to point out that as the work is in the public domain, they are free to do whatever they like with the property.

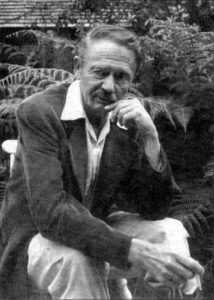

I wondered: Just what is it about this story that keeps speaking to people despite so much time passed and so many stylistic barriers? Lovecraft, even as he struggled, admitted that the book’s “macabre concepts” were “magnificent.” His fellow weird-fiction luminary Clark Ashton Smith was over the moon about it:

Clark Ashton Smith, master of the weird and Night Land devotee

“In all literature, there are few works so sheerly remarkable, so purely creative, as The Night Land. Whatever faults this book may possess, however inordinate its length may seem, it impresses the reader as being the ultimate saga of a perishing cosmos, the last epic of a world beleaguered by eternal night and by the unvisageable spawn of darkness. Only a great poet could have conceived and written this story; and it is perhaps not illegitimate to wonder how much of actual prophecy may have been mingled with the poesy.”

Well, all right, Ashton. Game on. I decided I’d better give this doorstopper a try.

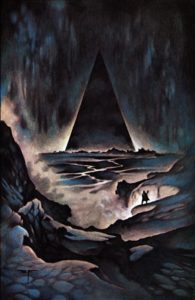

If you read a lot of classic science fiction or fantasy, it’s quickly apparent that The Night Land was far ahead of its time. Set in a bleak far-future world where the sun has slowly dimmed into an eternal night, the book brims with psychics, power armor, eldritch horror, arcologies, and post-apocalyptic gloom. The last remaining humans live inside a gigantic pyramid, a mile high and five miles wide, surrounded by all manner of soul-devouring monstrosities that prowl a wasteland heated only by vulcanism and geothermal vents. Inside the pyramid known as the Great Redoubt, cities lay stacked one atop another, powered and protected only by the obscure vagaries of the ‘Earth-current,’ a strange motive force that is no longer well understood by man. Such giant habitats are a staple of science fiction now, but in Hodgson’s time, the man who would give them their name—arcologies—had not even been born. Jack Vance is likewise considered the grandfather emeritus of the ‘Dying Earth’ subgenre, but The Dying Earth was not to be published until 1950, almost forty years later.

The pleasure of The Night Land does not lay in its characterization or its dialogue—for in fact the book has almost no dialogue, and its characters are stock archetypes at best—but instead in exploring the strangeness of its setting. One must develop an ear for the style of stories written in the pre-war period in much the same way one must develop an ear for the Victorians, or the Elizabethans–it does not flow naturally alongside modern works, which more often imitate the scene structures of film or television. Early twentieth-century pulp is an acquired literary taste, and the Night Land is an even more difficult beast. Given its denseness, there is a temptation to skim and speed ahead, but I found that the book is best enjoyed when one actually slows down the read, treating it less as a novel and more as a found document–the personal testament of a traumatized survivor, written in his own voice, with all the quirks and cadences of his actual speech.

The pleasure of The Night Land does not lay in its characterization or its dialogue—for in fact the book has almost no dialogue, and its characters are stock archetypes at best—but instead in exploring the strangeness of its setting. One must develop an ear for the style of stories written in the pre-war period in much the same way one must develop an ear for the Victorians, or the Elizabethans–it does not flow naturally alongside modern works, which more often imitate the scene structures of film or television. Early twentieth-century pulp is an acquired literary taste, and the Night Land is an even more difficult beast. Given its denseness, there is a temptation to skim and speed ahead, but I found that the book is best enjoyed when one actually slows down the read, treating it less as a novel and more as a found document–the personal testament of a traumatized survivor, written in his own voice, with all the quirks and cadences of his actual speech.

But make no mistake: For every fascinating piece of worldbuilding, there are four pieces of tedious repetition. Certain phrases to the extent of ‘you would have been so afraid!’ almost become leitmotifs, and I challenge you not to start keeping a running tally of the number of times ‘And lo!’ shows up in the latter sequences. Smooth reading, this is not. How much you’ll enjoy it depends entirely on how taken you are with the world itself.

The story opens on pre-modern Earth, with a narrator who begins to dream true dreams of his future self after the death of his beloved wife. But this frame story rapidly recedes into the background, giving way to a breathless tour of the perils and bizarre details of a bleak future, millions of years hence, where humanity can survive only in the deepest corner of a world whose surface was largely scoured away by an apocalyptic reckoning of mankind’s own making. Though many elements of the work are supernatural, its central conceit of a sun going dim was scientifically plausible by the theories of the time, fusion reactions not then being well understood.

Less scientific are the giant kaiju-esque Watchers that besiege the pyramid, and the dark unnamed Powers lurk between them. Only a rare few humans can send forth their psychic ‘mind-elements’ into the dark. The hero of the piece is one so gifted, and he soon discovers that another human settlement long believed lost yet perseveres in the night. Its own psychic is the reincarnation of the narrator’s love from the bygone days of old Earth—and when her far settlement begins to collapse, the adventure across the Night Land to rescue its people is on.

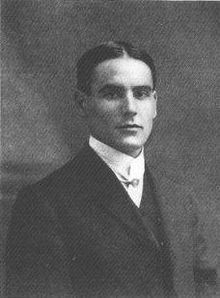

William Hope Hodgson

Hodgson’s personal life was not without its own adventures. As a thirteen-year-old, he ran away from boarding school to join the British navy; eventually he earned permission from his parents to attend formal sailor’s training and join the merchant-marine. His life on the seas seems to have been traumatic—he was to become a devoted body-builder to protect himself from abuse at the hands of senior mates, and later he wrote articles and gave lectures warning against oceangoing careers, citing low pay and cruel conditions. Most tellingly, when World War I broke out, he categorically refused any naval posting, even though this would have protected him from the meat grinder of the front lines. Nonetheless, he was a competent seaman; he received a medal for saving a fellow mate from drowning in shark-filled waters.

Moreover, nautical fiction—both supernatural and more mainstream adventure—was Hodgson’s wheelhouse. Works like The Ghost Pirates and the tales of Captain Gault have largely fallen into obscurity, but recent collections by Night Shade Books have brought many of these tales back into print. Weird fiction like The Night Land and The House on the Borderland is what has made Hodgson immortal, but it never made him successful. Hodgson worked in many genres, and it is striking how simple and unaffected his prose is in many of his adventure stories compared to the byzantine stylings of strange tales like The Night Land. I came away from my Hodgson survey with the impression that he was searching for his breakout hit—and never quite found it. In fact he repeatedly struggled with money in his lifetime, suffering at least one failed business and never quite achieving any comfortable income as a writer.

His fame may have grown as his writing matured—but we will never know for certain. Hodgson received a lieutenant’s commission to fight in World War I, and suffered broken bones and head trauma in 1916 that took him out of the war. Many men would be grateful to be free from that grisly conflict, but Hodgson was a different sort of man in a different sort of era, and he promptly re-enlisted as soon as his recovery was complete. Though lauded in writing by his widow and others for bravery in the field, the Great War did not long reward heroics. Hodgson took a direct hit from an artillery shell, leaving nearly no bodily remains.

The world will never know what else he might have imagined.

Leave a Reply